“Inanimate objects, do you have a soul?”

“Inanimate objects, do you have a soul?”

No, not a title of a sci-fi novel by Philip K Dick, that question was actually asked by French poet Alphonse Lamartine in the 19th century, and has never sounded more timely than when thinking about WALL•E; about the magic of animation that gave a personality – actually more, a soul – to a machine, a mere assembling of pieces of metal, circuits and wire, and managed to move audiences to the core. So, considering Pixar’s achievement, the answer to Lamartine’s question should have no hesitation: it’s a definite “yes”!

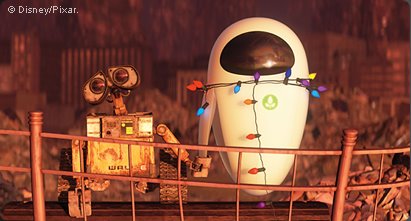

So then rises another question: “How on Earth do they do that?” That’s where we bring in Victor Navone, one of WALL•E’s many animators, and who happened to work on some of the key scenes of the movie, like WALL•E’s day at work, the red laser chase, WALL•E showing EVE his stuff (such as the Rubik’s Cube), their sitting on a bench at sunset, WALL•E’s space walk with the extinguisher and his being repaired by EVE back on Earth, among others!

An impressive display of remarkably animated scenes, by an artist actually not trained in animation! It’s in Fine Art that Victor got his degree, before working for several companies – including Presto Studios – as a designer, storyboard artist, story writer and art director. He also worked on Don Bluth’s Titan A.E. special effects. Yet, meanwhile, he was self-teaching animation, up to creating the irresistible short Alien Song, so impressive a job that it led The Lamp to call him. Victor now enjoys a full-time animator position at Pixar, with credits including every Disney•Pixar hit since Monsters, Inc and the brand-new upcoming Cars Toon series!

Naturally, we were very excited to speak exclusively to Victor about WALL•E and sneak a peek at Cars Toon, too…

Animated Views: First of all, please may you tell me about when you arrived at Pixar, and how you evolved within the studio?

Victor Navone: I started at Pixar in 2000 and was hired into the Development department to work on a project that was ultimately cancelled. From there I moved into the Animation department to work on Monsters, Inc., and I’ve been in the department ever since. I’ve also worked on Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, Cars, a tiny bit on Ratatouille, and a lot on WALL•E. I’m currently co-directing some interstitials for The Disney Channel featuring the characters from Cars. Each film has its own style, rules, and challenges.

Monsters was basically where I learned to animate in a production environment. On Nemo we had to learn how to make fish feel like they were moving through water, which means breaking some of the animation rules we normally observe. The Incredibles was our first time animating a primarily human cast, so we had to do a lot more research and planning for our shots. Cars featured much more simplified characters, so the challenge was to find ways for them to express themselves without limbs and spines, and also to show convincing car physics. Ratatouille had a very compressed schedule and very organic rat characters to master. On WALL•E, we had a similar challenge as on Cars, but without the luxury of dialog or facial controls.

AV: Why was it so important to you to work on Ratatouille, even for just one shot, when Colette is teaching roller skating to Linguini in front of Notre-Dame?

VN: Working with Brad Bird is a wonderful experience, as I learned on The Incredibles. I knew Ratatouille would be a great film, and I didn’t want it to pass me by completely.

AV: How did you come to work on Wall•E? Was that your choice, too?

VN: After finishing Cars and some promotional work I literally begged to be on WALL•E. I had heard about how different it was, and I’m a sci-fi fan, so it seemed like a good fit. I also wanted to get onto a film early in production, so that I could have a greater impact creatively.

AV: What were the challenges of such a project from your point of view, be it technically or artistically?

VN: We first tried to make WALL•E and all the other robots feel like machines with specific tasks, then we worried about how to make them emote and express themselves. It was often challenging to make their thought processes clear, and we always tried to find movements that were unique to the physiology of the robot, so that they wouldn’t feel like they were just imitating human movement.

AV: In The Art of Wall•E, Andrew Stanton wrote: “all the major elements that produce a film play a vital and unique role in telling the story. If you choose to remove one of them (in our case, the dialogue, which was drastically reduced), the other remaining elements must fill the void that is left behind. The job of communicating information suddenly becomes the imperative in every instance.” So, you had dialogue removed, but also some important animation parameters like squash and stretch that were removed, too since the robots are made of metal. How did you deal with that and communicate in such a subtle way while being deprived of certain means of expression?

VN: As daunting a task as this seems, that’s absolutely the kind of challenge that animators love. We enjoy bringing inanimate objects to life, and telling stories visually, rather than with dialogue. Luxo Jr. is a perfect example, and his character has a lot in common with WALL•E. WALL•E was the first feature were we really got to explore pantomime on a larger scale, but we’ve always done it in the past. There is always non-verbal communication happening in our performances, audiences are just more aware of it when the dialog is removed. As part of our preparation we referenced a lot of silent films, especially those by Buster Keaton. These were great inspiration for staging and communicating complex ideas and situations without dialog or even facial expression.

As animators we imagine the internal dialog or subtext in our minds, then try to play that dialog out visually in a sequence of actions that communicates clearly. For example, when WALL•E sees the red laser dot on the ground his first reaction is curiosity, then he gets a little scared when the dot quickly moves away. As he pursues the dot he tries to trap it with his hand, then he begins to think the dot is playing with him so he tries to scare it in a playful way. Then the chase is on. For this sequence of shots I tried to give WALL•E a natural progression of thoughts and emotions, and I also used the metaphor of a cat chasing a toy to help make the sequence more relatable and entertaining.

AV: When you animated WALL•E, you had just had a baby girl. Did her way of communicating help you animate the robots?

VN: Not at all, but it did provide other inspiration. I was assigned the scene where WALL•E wakes up in the morning and is trying to put his treads on like shoes. I wasn’t getting a lot of sleep at night because of the baby, so I had plenty of experience walking around my house in the dark, half-asleep,and bumping into things. I don’t think of WALL•E as “baby-like”, but more child-like and innocent. I think that definitely makes him appealing because it’s always fun to see the world through a child’s eyes.

AV: How did you express WALL•E’s personality via pantomime?

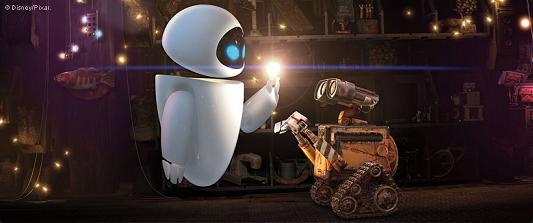

VN: That’s easier to explain by showing than by saying it, but I’ll try! With a limited character like WALL•E or EVE you have to rely a lot more on subtle changes and timing because you don’t have complex limbs or facial expressions to help the audience know what their attitude is. You can roughly suggest WALL•E’s attitude by the tilt of his head, the slump of his neck and the position of his shoulders, but movement is what really helps sell the idea. Seeing the change between two poses is as important as the pose itself. The Muppets are a great example of this; they don’t have complex facial expressions – usually just a mouth that opens and closes -and often they don’t have expressive hands. But based simply on how fast they move, the angle of the body, and the angle of their heads relative to their bodies we can tell how they are feeling, even with the sound turned off.

AV: Did you some research to prepare for your animation?

VN: We did a lot of initial research looking at real robots and machinery to establish a vocabulary of mechanical movement. Andrew’s mission was to make sure the robots felt like functional appliances first, and characters second. From there we would do exploratory animation tests for each robot to try to find their personality while still making them feel mechanical. Sometimes these tests would yield ideas that the director would like and put in the film. As I mentioned before, we also watched some silent films with Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin for ideas on silent acting and staging.

AV: You were in charge of certain sequences (differently from the traditional animation process, with one supervisor per character, usually). How did you manage to keep the character consistent all along the movie and at the same time infuse your own personality into the scene?

VN: This is how Pixar animators work on every film. It’s great because it gives us a variety of characters to work on and find our strengths and preferences. Ultimately one or two animators will demonstrate a strong proficiency for a certain character, and they will become the unofficial “leads” for that character. The director will often reference their work,and other animators will go to them for advice. It’s up to the director and supervising animators to make sure that all the animators’ performances are consistent from scene to scene. No two animators will have the exact same solution for a scene, but if they use the same vocabulary of movement to describe that solution, the performance should still feel seamless.

AV: Can you explain your process, your way of working?

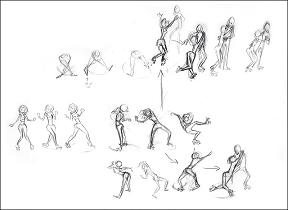

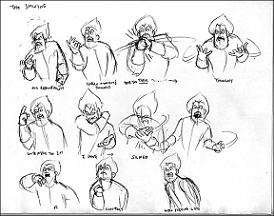

VN: We generally start with storyboards as well as the layout version of the scene, which is contains the CG camera, environment and props ready for animation. The director will explain what needs to happen in the scene, and what the important story and emotional beats are. From there I usually planned my scenes by exploring thumbnail sketches, then posed the computer models to match those drawings. Sometimes I had a really clear idea in my head and would just start blocking right in the computer. Once there is enough information in my scene to roughly communicate my ideas I show it to the director for feedback. He gives comments and I keep working, make adjustments based on his notes. I would usually show him a shot three or four times before it was pronounced “final”.

AV: What was the most challenging sequence you did on WALL•E?

VN: The most difficult sequence was where EVE revives WALL•E only to find that he has no memory. WALL•E himself was easy – he just had to be a machine without character. EVE was much more difficult. I had to plan out the entire sequence of her emotions and how they would progress over about 13 shots. I made a map of the whole sequence and plotted out her emotional state for every shot, and then tried to figure out how to communicate that through her body language and eye shapes. I worked back and forth with the director a lot on this, and made many revisions. He had a very specific idea of how he wanted the sequence to progress, and I had to try to match that vision. Often he would tell me to pull back, so that she didn’t get too frustrated or sad too soon. He wanted to make sure that she had somewhere to go emotionally, and that she went through all the appropriate states before she arrived at grief. It was a difficult balance to find. In the end, the sequence seems to go by so fast that I don’t even notice all the work I did!

AV: And the most exciting one?

VN: The most exciting was probably the scene in EVE Vigil where WALL•E and Eve are on the bench watching the sunset, and he’s trying to hold her hand. Andrew gave me a lot of room to explore the action, and play it like a guy on a first date trying to put his arm around a girl. I got to take it a lot further than it was played in storyboards.

AV: How was working with Andrew Stanton?

VN: Andrew was great, and was really open to good ideas, wherever they would come from. He would often let me add time to a shot so that I could include more acting ideas and entertainment. As animators at Pixar we always interface directly with the director for feedback on our performances, just like actors in a live-action film.

AV:You’ve just finished directing episodes of the Cars Toon series. What is the concept of the show?

VN: The series is called Mater’s Tall Tales and they’re all about the wild things that Mater supposedly did in his past.

AV:Was it difficult to put those characters typical of the Route 66 into a totally new environment like Spain (in El Materdor)?

VN: No, in fact it’s easier to come up with new story ideas once you put the character in a new environment. The Looney Tunes characters exploited this to great effect in the 40s and 50s.

AV:How was it working again with John Lasseter?

VN: Working with John is always fun. He brings a lot of energy and love for the Cars world, and he always has great ideas and suggestions. Rob Gibbs, also director on Cars Toons, and I did most of the day-to-day directing work, from working out the details of the story to approving the final lighting. We would show our progress to John every week to get his feedback.

AV:It seems to have been a great learning experience.

VN: Most of my experience at Pixar has been limited to the animation department, so this was a great exposure to the rest of Pixar’s workings. Also, you’re bound to learn a lot about filmmaking and storytelling when you’re being mentored by John Lasseter.

AV:How was it to come to lead a whole crew as a director?

VN: Animation at Pixar tends to be very collaborative, and we often give feedback on each others’ work. Nevertheless, it’s still only one part of the pipeline. It was a little intimidating at first having to direct all parts of the production, but I found that once I was sure about what I wanted it became a very fun and intuitive experience. I was lucky to have a great team of artists and technicians that I could delegate to, and who’s work always met or exceeded my expectations. That’s not to say it was never stressful; we had very short deadlines and limited resources.

AV:How different is the production of a TV series episode from a feature film?

VN: You don’t have as much time, money, or people, but because of these limitations everybody gets to contribute in more ways than they would on a feature. A lot of people played multiple roles, including myself. I was at times a director, supervising animator, animator, artist, and even a voice actor (but only for temporary dialogue).

AV:How many episodes did you work on?

VN: Three so far.

AV:How much of the material and software used in the original Cars movie did you use on the series?

VN: We had to revert to the software we used back on Cars because the current version doesn’t work with those old models. We were able to adapt a lot of our latest lighting techniques and technologies, but otherwise it was like going back to 2005. We had access to all the old characters and sets, but we ended up building lots of new assets as well. Mater also gets lots of new paint jobs and costume elements.

AV:How would you describe your average working day on the series?

VN: It seemed like most of Rob’s and my time was spent in one of three places: meetings about planning, scheduling, and other boring stuff; reviews of work done by modelers, animators, artists, lighters, etc; and Editorial, where everything came together. I was surprised at how many decisions about story and direction were made in Editorial, together with our Editor, Torbin Bullock.

AV:How did you build up your crew? As an animator, was it easier to direct colleagues of yours?

VN: The producer, Kori Rae, was responsible for assembling the team. It was a little weird directing my fellow animators at first, but everyone had a good attitude and I tried hard to foster a sense of teamwork and collaborations. I think everyone had a good time!

AV:You did the sound mixing at the legendary Skywalker Ranch. How was that?

VN: Skywalker is a beautiful place to visit. It’s a shame to have to go inside and work when you’re there. John, Rob and I worked closely with sound designer Tom Myers to mix the score, dialog and sound effects for all three shorts. We also got to attend the music recording sessions with composer Bruno Coon, which was a treat. I found that in sound mixing, like many things, less is more. We spent more time taking out sounds and simplifying things than we did adding details. If you have too many sounds it starts to compete with itself and the music and you end up with noise.

AV:How did you choose Bruno Coon as the composer of the series and how did you work with him?

VN: Bruno Coon is the sound editor and arranger for Randy Newman (who did the score for Cars). We would watch the story reels together and explain to him what emotions we were after in the different scenes. He would send us rough drafts of music for our feedback, and once we were satisfied with his solutions we recorded the music at Skywalker with live musicians. Bruno gave us some great varieties of music, from 70s funk to Sousa-style marching band to flamenco. All the music and themes for these shorts are original.

AV: Anything you’d like to add on the series?

AV: Anything you’d like to add on the series?

VN: They were fun to make. I hope they’re as fun to watch!

AV: Many Pixar artists have, in addition to their job at the Studio, artistic side activities, like Enrico Casarosa or Ronnie Del Carmen, who are part of Sketchcrawl and are doing comics and paintings. What about you, aside from your position at Pixar?

VN: I don’t really have any side projects anymore, because I just don’t have time! Family and work keep me very busy. I draw a little, and I’m learning guitar, but that’s about it. I do teach with AnimationMentor.com, which takes up a lot of my extra creative energy.

AV: On your signature, you write “2-4D artist”. What are the relations between all these dimensions of art, from 2D to 3/4D?

VN: My traditional artwork as 2-dimensional, 3-dimensional refers to computer graphics, and the 4th dimension is time, which makes animation possible. Both my 3D and 4D work are heavily influenced by the principles of 2D art, especially in the areas of composition, design and posing.

AV:What are you ready to do next?

VN: Right now I’m thinking about vacation. A nice, long vacation…

Victor Navone’s ALIEN SONG can be viewed online here.

Thumbnails by Victor Navone, reproduced with kind permission, with all our gratitude and admiration. All artwork ©Disney•Pixar.